Reflections on Writing a Biography

Our hero, in despair, sits in his comfortably positioned armchair, gazing at the gleaming light reflected off the metal reinforcement of the brushes, the dried resin's golden hue, and the other tools of his trade. He avoids looking at the poorly started landscape. He decides that he won’t look at it for weeks. He thinks it should be turned toward the wall. But he doesn’t move, as failure paralyzes him.

Such moods are rarely spoken of by painters. He knows well that in a few months, it will be worth revisiting the same piece. He might find something that will inspire him to continue. This thought softens him a little.

Most artists’ careers don’t rise steadily upward; moods and fleeting bursts of enthusiasm break the trajectory.

Dési is a fond memory. Tamás Ervin and Papp Gábor were his mentors. Four years of charcoal and pencil drawing studies. A studio photographer, because he had to make a living somehow. Then came Artex (a company exporting artwork to the West).

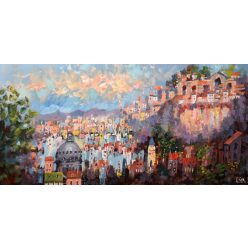

He longed to gaze at Robert Rauschenberg's pop art works. In the alleyways near the Academy of Fine Arts (now a university), neglected houses from the turn of the century stood. He savored the dusty greys and brick reds of the peeling plaster. A sharp-eyed art student framed some damaged details with white chalk, which created the illusion of a complete picture. He felt that the idea had been stolen from him.

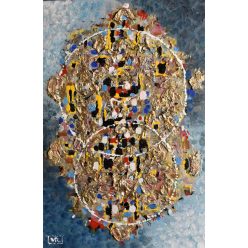

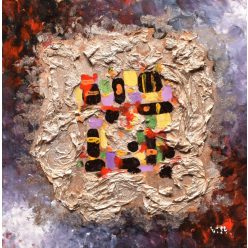

He experimented with new materials and user-friendly technologies: scattered silver dust, drops of linseed oil. Interesting silver, yellowish spots. Then came coarser paper, sand mortar. It was good, but where were the colors? Disappointment upon disappointment. Sometimes, a broken sentence can be very revealing. The areas left white on the canvas create an expectant tension.

Two years later. The two-year anniversary finds our painter in a similar mood to when he painted that particular landscape. This time, a portrait of a woman stares at him from a canvas propped against the wall. He agreed to paint it at the model's urging, sometimes pleading, sometimes sulking. From memory, he traces the features on the woman’s face, those details that could transform the experience into a painterly passion.

A tired-faced woman with two ugly children. This is Holbein.

Eva doesn’t have children, but her face is indeed tired. Let the final result be one that both she and the painter want to see! A hint of life in the eyes, bangs, parted, moist lips, a touch of coquettish charm. Let’s not go too much in the direction of Renoir! Yes, there’s no virtuosity here. Perhaps a decent, craftsperson's job. This studio is cozy. Eva will be satisfied. She will get the portrait, and the artist, with his split conscience, will find peace.

May Saint Luke help us, painters, and not least, the leaders of the guild!